The origin of the acronym, TINA (or There is No Alternative) is credited to the late British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, the Conservative Party leader who was in office from 1979 to 1990. Thatcher used it as a slogan to lend credence to her belief that there was no alternative to a market economy where free trade and free markets were the only way to build and distribute wealth. Later, the phrase “TINA factor” was appropriated by Indian political commentators who have used it to describe situations where one powerful party or head of government seems so strong that there seems to be virtually no alternative to replace him or her.

Famously, the phrase was used for the late Indira Gandhi who was the second longest-serving Prime Minister of India (she served from January 1966 to March 1977 and again from January 1980 until her assassination in October 1984). More recently, even as the present Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, is serving his second term, the phrase has been cropping up again with various political analysts speculating whether there is a TINA factor at work and whether there is in reality no alternative to Modi.

With the near decimation of the only other significant national party, the Indian National Congress, which after decades of being in power, is now reduced to holding a mere 52 of the 543 seats in the Lok Sabha; and 36 of the 245 seats in the Rajya Sabha, the question of whether the Modi-led, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-dominant regime has anyone to challenge it in elections. In addition, the BJP, or alliances in which it participates, is part of the government in 18 of India’s 31 states and Union Territories and the party has publicly proclaimed its mission to have a “Congress-free” India.

In the absence of a comparably strong and cohesive party to challenge the BJP at the national level, the alternative in the form of a challenger could, at least theoretically, be a coalition of parties—strong regional ones or one that can be led by the Congress but comprising many smaller parties. Some political analysts have punted for the Mamata Banerjee-led All-India Trinamool Congress (AITC) as a possible key player in evolving a coalition of regional parties. That view has gained ground in the aftermath of the recent West Bengal elections in which despite the BJP’s deployment of a high-powered campaign, Ms. Banerjee comfortably cruised to victory, effectively retaining chief ministership for the third term.

ALSO READ: Mamata In A New Challenger Avatar

Stable coalition governments are common in many parts of the world, including, in particular, in Europe where in countries such as Switzerland, Finland, Belgium, Italy, and Germany, it is almost a given. In India, both at the national as well as the regional levels, coalitions are not novel arrangements. They have been tried but the outcomes, at least in terms of stability, have been mixed. Unless led by a single party that has a significant clout in terms of the number of seats it wins in Parliament, coalition governments have been short-lived in India. In 1996, after a fractured electoral verdict, when the BJP, led by the late Atal Bihari Vajpayee, emerged as the single largest party in Parliament and was invited to form a government and cobble together a majority (by wooing other smaller parties), it failed to do so and collapsed in 13 days.

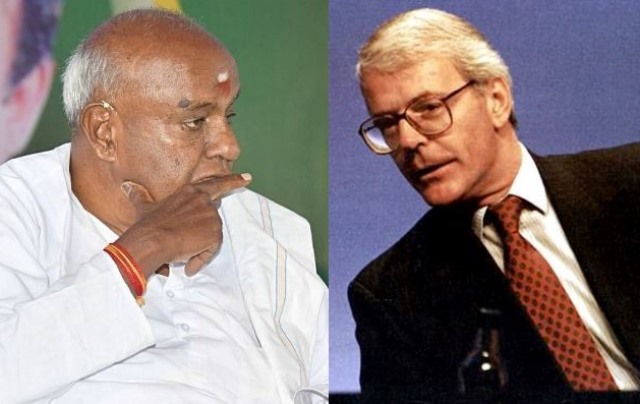

It was replaced by the United Front, which was closest to a copybook version of a political coalition with 13 different parties coming together to form an alliance. The coalition formed two governments between 1996 and 1998, the first headed by Prime Minister H.D. Deve Gowda, and the second by I. K. Gujral. The United Front managed to stay in power for less than two years.

The current crisis in terms of finding a worthy challenger to the BJP is accentuated by the fact that the Indian National Congress’ strength has been getting dissipated over the past few years. Its leadership, which for all practical purposes, rests with the Nehru-Gandhi family, has been unable to provide either cohesion or expansion. Rahul Gandhi, who briefly became head of the party between 2017 and 2019 has been an enigmatic leader, often appearing reluctant or indecisive. In recent months, the party has witnessed an exodus of key young leaders, many of whom could have been groomed to lead the historic party whose origins go back to 1885. Many of these young leaders have left to actually join the BJP, the Congress’ arch rival.

ALSO READ: Can Socialism Find Its Feet?

Partly it is hard to make the concept of a coalition government functional at India’s national level because of the nature of the nation. India is a pluralistic society that is like few others. The sheer diversity of a country with a population of 1.4 billion that is more like a continent made up of several “countries” is what makes things particularly difficult when it comes to forging alliances between different parties. The differences in languages, cultures, economic development, among several other parameters, is so wide-ranging that very often it is difficult for outsiders to grasp the enormity of the complex politics in the country. There are differences between regions (north and south, is an example); between states that can be neighbouring ones (each of the southern states has a different language); and between castes and gender.

Coalitions work better in countries where the population is small and less diverse. In Europe, governments made up by alliances of political parties with seemingly different views and ideologies have been comparably more stable than similar arrangements in India. Besides being easier to govern because of their size (some European countries have populations that are smaller than those of large Indian cities), the degree of plurality when it comes to ethnic diversity, cultures, language, and so on, is much smaller than those that exist in India.

To be sure, however, even the ruling BJP-led government is a coalition. Modi is the Prime Minister of a coalition government formed by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which comprises at least 14 different parties. Besides being united by ideology (most of the NDA’s constituents are right wing oriented), in the BJP it has a powerful leader: of the 334 seats in Lok Sabha that the NDA now controls, 301 are BJP members. That is the kind of strong glue that makes coalitions work in India. For regional parties, such as Ms. Banerjee’s AITC, it can be difficult to achieve a position where it can provide such a cohesive glue. The same goes for other regional parties such as, for example, the Samajwadi Party or the Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh; or the Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar. All of them have the potential to score electoral victories in their respective regions but have little political leverage when it comes to making it big on the national scene.