Award-winning filmmaker Vinod Kapri speaks about his book that documents movement of migrant workers amid lockdowns and his interaction with Danish Siddiqui

How did the idea of your book ‘1232 km: The Long Journey Home’ come about?

I am basically a film-maker and never thought of writing a book. When the first nationwide lockdown was announced in March 2020, I was expecting this kind of migration and discussed this with my journalist friends that the government was probably not aware of the problems of the daily wage labourers and this is going to be the biggest exodus. My fears came true. We saw millions of people on the road. Being a storyteller I felt I needed to document this journey.

During that time, the mainstream media, except a few, were focused on Tablighi Jamaat incident. I felt it was an injustice to these workers and thought I should be a part of one of the journey. I travelled with them for seven days on the trot, filming whatever I could. Back home, while I was editing the documentary, I realised it did not tell the complete story. It was then that I thought I should write a book because there were moments and feelings that the camera could not capture. That is how ‘1232 km: The Long Journey Home’came about.

What did you learn from this experience?

I would admit that I was not aware of the migrant labourers beyond the work they did. I knew nothing about their families and the challenges they go through staying away from home. After completing the journey with them, I realised the middle or the privileged class never really thought about these people who have been a part of their lives, run our society, build our cities, clean, cook, iron, do carpentry and plumbing work, operate lifts and guard our apartments. We don’t know anything about them their families, their villages. They are nameless and faceless. My journey completely changed that.

But for holding the mirror, you were heavily trolled on social media…

There are a few people whose job is to target, abuse or demoralise people holding the mirror. But largely, it is like a hit job for a political ideology. The trolling is very manufactured, targeted and organised syndication. Whenever we write something, post something in public domain, we are aware that a section of users will troll us, pull us down and try to play dirty, all lies. So it doesn’t really matter. You are not answerable to them. It is our duty to tell the truth and state the fact. To not speak up today means our future generation will be ashamed of us.

When the second wave of Covid-19 started, I was on the field documenting it. I saw people dying in front of me, I was in and out of hospitals, at various cremation grounds, shamshan ghats for almost 32 days and covered it extensively. It shook me to see the suffering, the irreparable loss, relationship and emotions.

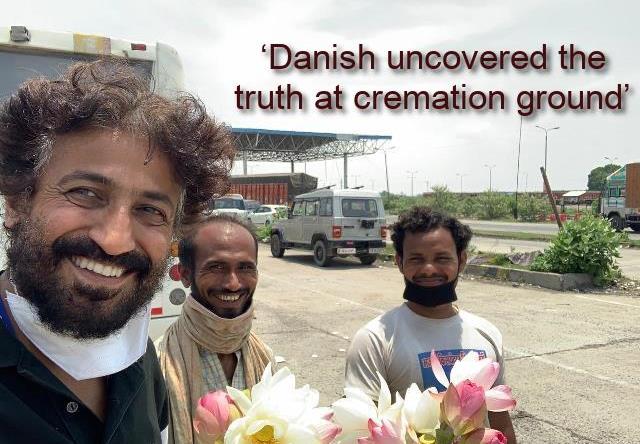

And you met Danish Siddiqui at one of those cremation spots… taking pictures that will later draw both anger and admiration.

I met Danish Siddiqui when he was taking photographs of the funeral pyres at a cremation ground in Seema Puri, at eastern border of Delhi. It was my only meeting with him and I was not aware that he is working with Reuters. We had a small conversation and I told him I was documenting the pandemic. He asked me for which platform was I working. To which I replied it is yet to be decided, and I was just shooting. I asked him what was he working for and he said he was just clicking.

His pictures did receive a lot of backlash. But imagine if that picture of Danish did not exist, how the world would come to know the ground reality. That picture created shivers in people’s mind. I agree partly that death is a solemn moment that needs privacy. But the issue of privacy is secondary when thousands are dying and the government is a mute spectator. The critics used religion to target Danish merely to hide the ground reality.

Danish lost his life in a warzone. Do you think journalists should draw a line…?

No one knows where to draw the line. We can’t predict our death. We may die due to a heart attack at home too. As a journalist, we should uncover the truth. That is the lakshman rekha we should not cross. For that if we end up losing our lives then be it; consider these as professional hazards that we have to face in the line of duty. Just the way frontline workers and doctors are losing their lives in this pandemic, they cannot choose to draw a line for their role…they have to go out and treat patients.

And holding those in power to account is your duty?

Absolutely. As a journalist and storyteller, we are considered as the fourth pillar of democracy and it is our right to question the government of the day, be it the BJP, the Congress or any other political group.

– Interview by Mamta Sharma