Is phone-tapping par for the course? And is Covid a more deadly virus for the economy

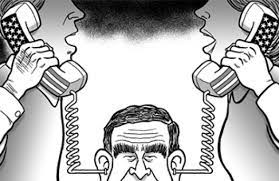

The news that hundreds of Indian phone numbers appeared on a list selected for surveillance by clients of NSO Group, an Israeli firm, rocked political and media circles last week. The reaction, predictably, was one of high indignation. One international publication even labelled it as “India’s Watergate moment”. But first, the facts. Last Sunday, the Pegasus project, a consortium of media including the Guardian, Washington Post, Die Zeit, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Le Monde, and the Indian digital publication, Wire, revealed that government clients around the world had used hacking software developed and sold by Israeli surveillance firm, NSO Group, to target human rights activists, journalists, and lawyers.

Among the government clients was the Indian government. It was revealed that of the 50,000 phone numbers that were targeted by the phone spyware, more than 300 belonged to Indian politicians, journalists, and human rights activists. International and domestic media organisations–the former more than the latter–were quick to issue a scathing condemnation of the tapping of phones by governments, including in India, which prides itself as the largest democracy in the world.

The Israeli firm says it licenses the software to government agencies only to combat terrorism and other serious crimes. In India, its use has been for other reasons: among those whose numbers appear on the database are politicians (belonging to the opposition as well as the ruling regime); journalists; activists who oppose the ruling regime; and others.

The outrage over the Pegasus Project’s revelation is understandable. Phone-tapping is a violation of the privacy of the extreme kind. Last week, the Editors’ Guild of India, which has the twin objectives of protecting press freedom and raising the standards of editorial leadership of newspapers and magazines, demanded a Supreme Court supervised inquiry into the Pegasus controversy. Opposition parties to have been up in arms. The Indian government has, predictably, denied any misdoing. India’s home minister Amit Shah has attempted to dismiss it as a “report for disruptors for the obstructors”, implying that it is an attempt by obstructers who are foreign organisations that do not like India to progress and disruptors who are Indians who are opposed to the government.

Be that as it may, the fact is that phone-tapping and other means of surveillance of opposition leaders, journalists, activists, and others, have a very long history in India.

Long before the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power, phones of prominent individuals were routinely tapped by successive Congress-led regimes. Way back in 2010, the senior BJP leader L.K.Advani attacked the then Congress-led UPA government, alleging that it was tapping the phones of senior political leaders in what he described as the “return of Emergency”.

Unfortunately, cynical as it may sound, phone tapping and other means of surveillance by governments are routine procedures followed by India’s authorities–they could be governments, both at the centre and in various states; and they could be investigating agencies. Way back in 1988, a chief minister of Karnataka had to resign after charges were brought against him of tapping phones of many of his opponents as well as allies; in 1989 when V.P. Singh was the Prime Minister, it was alleged that his government was tapping the phones of rivals. More recently, in 2010, at least 100 tapes of recorded telephonic conversations between a corporate lobbyist (Niira Radia) and politicians, journalists, and businessmen, were leaked, creating a furor. In reply to a Right to Information query in 2013, it was revealed that around 9,000 phones and 500 email accounts were monitored every month by the UPA government.

Sadly, and this is the most cynical cut to the entire sordid story, nothing really has changed. Few in Indian media or political circles, except for the haplessly naive, are surprised by the latest allegation that the government has been using spyware to snoop on people. It is as if something that is grossly violative of personal space and the right to freedom of speech is accepted with a shrug–an attitude that doesn’t sit well with the principles of democracy that we often uphold with pride.

Covid hurts the Indian economy hard

Quick, how many people in India live below the threshold of poverty? If you said 812 million, which is 60% of the population of India, you are, well, wrong. The World Bank considers anyone who lives on less than US$3.2 a day as being below the poverty line for lower and middle-income countries. And, pre-Covid, the number of people estimated to be below that line was 812 million.

Not any more. Projections based on analysis conducted at the United Nations University show that in the aftermath of the two waves of Covid, an additional 104 million Indians could fall below the poverty line.

It may seem heartless but although (officially), approximately 420,000 people are said to have died of Covid-related causes in India, it is not an alarming statistic. At least not so, relatively speaking. India’s deaths per million people are 301; the USA’s is 1879; Brazil’s is 2548, and Germany’s is 1094. Distilling down human suffering and deaths down to statistical comparisons can seem patently insensitive but the fact is India’s economy has been worse hit by Covid than its people have.

That last sentence should be qualified because when the economy is hit, the people suffer. But Covid’s direct impact on the health and mortality of Indians is far less by many degrees than its indirect impact will be. Last year (the fiscal year that ended on 31st March), India’s GDP shrank by 7.3%. And, if 104 million Indians have joined the ranks of the extremely poor, which would then mean 65% of Indians are below the poverty line as defined by the World Bank, rest assured that many millions more have slid down the ladder of economic status. Many more millions have slipped from being in the higher segments of the middle-class to its lowest rungs.

Much of this can, conveniently, be attributed to the pandemic and its wrath but that would be wrong. India’s economic fundamentals are to blame. Its economic policies, which have been bereft of a long-term vision or big bang reforms, are to blame. When widely publicised news and visuals portrayed Indians gasping for oxygen and hospital beds, Covid showed how flimsy India’s healthcare infrastructure was. It has now shown how ramshackle its economy is.